Typically, if the government is going to institute deportation proceedings on the basis of a criminal charge, there must be a conviction. In immigration court, the term “conviction” is interpreted very loosely. For example, in the State of Florida, if a person receives a “withhold of adjudication,” they are technically not convicted, even though they have pled no contest or guilty and receive some form of punishment. However, in immigration court, a withhold of adjudication would serve as a conviction sufficient to form the basis of a removal order. This has been pretty well established in the immigration law community for some time. What hasn’t been established is whether a person can be deported when there has been no formal conviction in criminal court, but the non-citizen admits to the elements of the offense before a criminal law judge.

The Fourth Circuit has recently spoken on this issue in Boggala v. Atty Gen’l, No. 16-1558 (4th. Cir. 2017). Vijaya Boggala, a citizen of India, was arrested for solicitation of a minor. He entered into a deferred prosecution agreement with the state. A deferred prosecution agreement is basically front loaded probation. It is an agreement to complete certain conditions (i.e. probation, counseling, etc.) and the state agrees to drop the charges upon successful completion of those conditions. In this case, Mr. Boggala was required to admit to elements of the offense in open court before a judge, which he did. He then successfully completed all the conditions of his deferred prosecution agreement and the charges against him were dropped. You wouldn’t think that he would be subject to deportation, right? After all, the charges were dropped. Despite not being convicted of the crime, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) instituted deportation proceedings against Mr. Boggala. They charged him with being deportable under INA Section 237(a)(2)(A)(iii), as an alien convicted of an aggravated felony, and under INA Section 2237(a)(2)(A)(i), as an alien convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude. The question presented to the Fourth Circuit was whether Mr. Boggala was “convicted” of the offense as that term is interpreted under the Section 237(a)(2) of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Section 101(a)(48)(A)(i) of the INA defines “conviction” as a “a formal judgment of guilt of the alien entered by a court or, if adjudication of guilt has been withheld, where…the alien… has admitted sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt.” The Fourth Circuit thus analyzed whether Mr. Boggala admitted sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt and not whether the court actually made a finding of guilt. The Court found that because Mr. Boggala stipulated to the facts that were to be used against him, he was convicted within the meaning of Section 101(a)(48)(A)(i), despite not having been convicted in criminal court.

Florida Immigration Lawyer Blog

Florida Immigration Lawyer Blog

So many lawful permanent residents (greencard holders) put off becoming a United States citizen for a variety of reasons. Whether they don’t want to pay the fee or go through the administrative process or study for the test or renounce their loyalty to their country of birth, they put off becoming citizens. This is a mistake. Once you become a United States citizen, you can disregard the Immigration and Nationality Act. This means that you can come to and go from the United States as any other U.S. citizen does. This means that if you are ever convicted of a minor crime, you would not be deportable. This means that you would not have to deal with the hassle and uncertainty of being inspected by Customs and Border Protection agents in the same way as non-citizens, including random secondary inspections. If you wanted to reside outside the United States with the option of coming back, you could do this as a United States citizen. You may be able to apply for your non-citizen relative or help keep that relative from being deported, if you are a U.S. citizen. The naturalization process takes several months and often times it can be too late for people to apply when they need it. For example, if you are arrested for battery, minor drug possession, theft, criminal mischief, fraud, or any other criminal charge, it could prevent you from applying for citizenship for 5 years, and sometimes forever. Or even worse, it could be a basis for deportation, no matter how long you have lived in the United States and been a lawful permanent resident. The immigration laws are complicated. Do yourself a favor and become a U.S. citizen as quickly as possible.

So many lawful permanent residents (greencard holders) put off becoming a United States citizen for a variety of reasons. Whether they don’t want to pay the fee or go through the administrative process or study for the test or renounce their loyalty to their country of birth, they put off becoming citizens. This is a mistake. Once you become a United States citizen, you can disregard the Immigration and Nationality Act. This means that you can come to and go from the United States as any other U.S. citizen does. This means that if you are ever convicted of a minor crime, you would not be deportable. This means that you would not have to deal with the hassle and uncertainty of being inspected by Customs and Border Protection agents in the same way as non-citizens, including random secondary inspections. If you wanted to reside outside the United States with the option of coming back, you could do this as a United States citizen. You may be able to apply for your non-citizen relative or help keep that relative from being deported, if you are a U.S. citizen. The naturalization process takes several months and often times it can be too late for people to apply when they need it. For example, if you are arrested for battery, minor drug possession, theft, criminal mischief, fraud, or any other criminal charge, it could prevent you from applying for citizenship for 5 years, and sometimes forever. Or even worse, it could be a basis for deportation, no matter how long you have lived in the United States and been a lawful permanent resident. The immigration laws are complicated. Do yourself a favor and become a U.S. citizen as quickly as possible. In some cases, you may be able to file a Petition on behalf of your non-citizen spouse or other family member, even if they are here without authorization. For example, a spouse of a person who came into the United States without authorization may be able to file a petition and that person may be able to file a provisional waiver to excuse their unlawful presence in the U.S. An approved petition alone could help if the person is placed in removal proceedings or taken into custody by ICE. The immigration laws are designed to be more forgiving of certain immigration violations if the person is an immediate relative of a U.S. citizen. Filing a petition may or may not be beneficial in your case. Consult with an immigration attorney to see whether it would help or hurt you or your loved one.

In some cases, you may be able to file a Petition on behalf of your non-citizen spouse or other family member, even if they are here without authorization. For example, a spouse of a person who came into the United States without authorization may be able to file a petition and that person may be able to file a provisional waiver to excuse their unlawful presence in the U.S. An approved petition alone could help if the person is placed in removal proceedings or taken into custody by ICE. The immigration laws are designed to be more forgiving of certain immigration violations if the person is an immediate relative of a U.S. citizen. Filing a petition may or may not be beneficial in your case. Consult with an immigration attorney to see whether it would help or hurt you or your loved one.

Many potential clients who call our office ask this question: Why do I need to pay for a consultation with your immigration attorney? There are two easy answers to that question. First you get what you pay for. And second, an attorney’s time and knowledge are what they have to offer to a client. If an immigration attorney is willing to do a comprehensive telephonic or in-person consultation on every immigration case for free, that may not be the attorney you want to handle your case.

Many potential clients who call our office ask this question: Why do I need to pay for a consultation with your immigration attorney? There are two easy answers to that question. First you get what you pay for. And second, an attorney’s time and knowledge are what they have to offer to a client. If an immigration attorney is willing to do a comprehensive telephonic or in-person consultation on every immigration case for free, that may not be the attorney you want to handle your case.

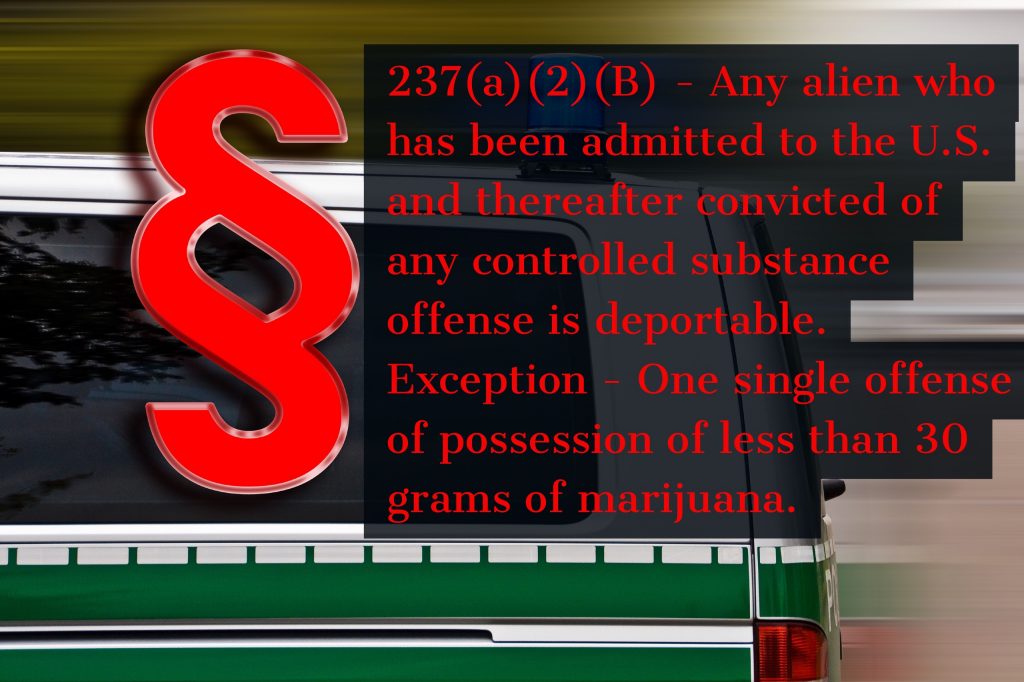

There are very few forms of relief available which would allow an immigration judge to waive or cancel this basis of deportation. You are either eligible for these forms of relief or you are not. If you are not eligible, the immigration judge has no discretion to block your deportation, even if he or she wants to.

There are very few forms of relief available which would allow an immigration judge to waive or cancel this basis of deportation. You are either eligible for these forms of relief or you are not. If you are not eligible, the immigration judge has no discretion to block your deportation, even if he or she wants to.